The year 1972 signaled the beginning of a period that would change not only the lives of Filipinos at that time, but also the course of Philippine history altogether. On September 21, former President Ferdinand Marcos placed the country under Martial Law. To this day, almost half a century later, the country is still divided in its stance against this pivotal period.

Statistics from the said period paint an era of growth and development, yet more recently collected data portray a time which led to crippling debt and reports of brutality. When collected fairly, numbers do not lie. Facts are irrefutable; moreso, they are objective and without bias. But perhaps what makes numbers so unrelatable and so impersonal is precisely that—their lack of a form of human compassion. Perhaps this is why people find it hard to believe numbers and to trust in them. Perhaps personal accounts will allow us to better understand what transpired in that period.

When the topic of Martial Law arises, there will always be more than one side of the story. The authenticity of each account is incontestable and absolute, which is why we need to hear out every perspective, for an experience is a manifestation of the truth for the person involved. And frankly, no amount of dissuasion or discussion can alter what a person finds to be his or her own truth.

A Progressive Perspective

“Peaceful” is the word which came up the most when I asked my dad about his experience during Martial Law. Only ten at that time, all he could remember was the unmistakable peace and quiet that was apparent throughout the streets. As a child, he was fascinated with the military trucks patrolling the streets.

“I recall waiting by the window every morning…for the military men to drive by,” he mused. Alongside this childlike wonder was a fear of the undeniably unordinary things occurring around him. “Cable TV only featured government-approved channels and broadcast stations. People were afraid to leave their houses.” he said. Though fascinated, he was also very much afraid of what was happening. He recalls that the atmosphere had this undeniable tension to it.

“It felt as though war would break out at any moment.”

“My parents [attempted to comfort my siblings and I by reassuring us that since [my] auntie worked for the government and was connected to all the right people, that we would be safe.” To my father, that was not much of a reassurance. Since the only sources of news were controlled by the government, he was not aware of all the atrocities which transpired during that time. He could only assess the situation through the things he could see firsthand. The curfews allowed for safer and quieter streets. Little to no stories of crime were ever heard of.

“Your angkong, who was then a retailer of alcohol and canned goods, experienced nothing but convenience with the implementation of the Martial Law.” He stated. To him and to any other law-abiding citizen, as far as they were aware of, Martial Law only brought with it good things.

They did hear news about rallyists and protestants who were jailed during that time. “At a young age, I was aware that being jailed without the proper juridical processes was wrong,” he continued, “but the media painted those people as… extremely volatile and harmful [to] the country, to the point that we were made to believe that they were nothing more than that.” These rebels were portrayed as mere, unavoidable hindrances to the peace Martial Law effectively provided. They started seeing these people not as human beings, but solely as casualties to a war against criminality.

“I realize [when I grew older] that maybe the Martial Law wasn’t all that good.” During that time, he saw nothing wrong with what happened, perhaps because he was looking at it from such a narrow perspective—one that only included his immediate environment. He realizes now that since his immediate family was never really harmed in anyway, he forgot to consider the circumstances other people faced.

To the other Filipinos whose loved ones were never harmed, Martial Law actually provided them safety and peace, so why wouldn’t they support it? However, what we all have to understand is, we as citizens and as people should never think that human lives exchanged for any perceived notion of safety, order, or development is an acceptable trade. Accounts of rape, torture, and murder were never confirmed and only transpired through hearsay during the time of Martial Law. This equivocal aspect of what transpired during that time is one of the reasons why my mother’s disdain towards Martial Law then was not as firm as it is now.

Resurfacing Regrets

My mother remembers constantly living with an unsettling feeling of fear and anxiety. “Nobody dared to mention or to even think about the Marcoses.” she expressed. Phone calls were direct and to the point because people were afraid of possibly saying something that would displease whatever uninvited party whom might be tuning in on their conversations. During that time, she and her family saw these instances as minute sacrifices for a life of guaranteed safety and peace.

She eventually found the stiffness of having to always be aware and careful of the things you do, the things you say, and the people you associate with fade into everyday life. No news of atrocities and cruelties ever reached her knowledge. She thought that everyone else in the country was experiencing the same reassuring peace that she was.

Two specific instances led my mom to be more critical of the controversial period. “On my way to my university to enroll, I was held at gunpoint for my money.” She expressed that never in her life had she felt more powerless nor more insignificant than in that specific moment. She felt as though her life and her future were in the hands of someone she did not even know. “I waited for the soldiers to come marching to my aid, but none ever came.” She reluctantly gave up the money in exchange for her life and went home visibly shaken by the experience.

Days after, her mother was arrested for playing mahjong with her friends in her private home. “Your gua-ma, who was already in her late sixties at that time, was dragged to Camp Crame with her friends to hand-pluck weeds from the field within the military compound.” she shared, shaking her head in disappointment. “They were let out the morning after, but seeing my mother made to accomplish such an irrational task certainly stirred something in me—but never enough for me to speak out.”

“All around me, people my age—the youth of that time—were going up in arms to rebel against the dictatorship.” As the rallies grew larger and the protests more intense, more and more news transpired by word of mouth. Accounts of rebels being arrested, jailed and never to be heard from again deterred my mother from ever joining in. Now, she regrets having never joined any of the protests.

“I [felt] so cheated by the fact that for a long period of time, I was deprived of the truth.” She added,

“I hated the fact that I was made to believe that the Martial Law was something heaven-sent when in fact, so many people were living in hell.”

Venturing Beyond the Wall

The stories of both my parents bear striking similarities. During the Martial Law, neither thought anything particularly vile was happening simply because they had no means to know otherwise. Having to look back to what they know now as a very dark time triggers a sense of inner turmoil, wherein they cannot come to terms with why they were so nonchalant with the subject of Martial Law, given that so many terrible things happened.

This might be one of the many reasons why so many Martial Law supporters find the need to nullify or to invalidate personal accounts of people who were mistreated during that time. Experiencing cognitive dissonance is actually a good thing in the sense that this disconnect only occurs when the people experiencing it feel something fundamentally wrong with their opinion in relation to new found information.

To try to resolve this unsettling discrepancy between personal opinions and what is perceived to be right and wrong, people either attempt to discredit the new information or they try to convince themselves that something as horrific as deception, rape, torture and murder are but small prices to pay for alleged national advancement. Another way people get around this form of dissonance is to avoid the source altogether by displaying apathy towards anything remotely related to the issue at hand.

Anyone who has experienced anything similar to this, whether they be for or against Martial Law, knows that there is a part of them trying to recalibrate and adjust, that there is a part of their humanities fighting to emerge. This does not mean though, that cognitive dissonance should stop the people who experience it from ultimately coming to terms with the brutality of Martial Law. Although being deprived of the truth excused them from being apathetic then, it does not excuse them now from being aware of and trying to defend other people’s humanities.

Hearing my parents discuss their experiences during this time was very eye-opening for me. As a family, we are used to talking about political issues. Oftentimes, there is disagreement, especially between my sister and I and my parents. There seems to be a barrier between the two groups, perhaps due to our differences in age. My sister and I were quick to dismiss any pro-Martial Law talk as being backwards and lacking the initiative to be more compassionate.

After hearing how unaware they were made to be during that time, I cannot blame them for not being entirely against Martial Law.

Their explanations made me realize that the people who experienced Martial Law were conditioned to be silent, to be selfish, and to be passive by one very compelling threat: death.

The death of not only themselves, but the death of the people they loved as well. This continual need to suppress any urge to fight, to speak out, crept its way into their subconscious and conditioned them to feel apathetic. And this, although unchangeable, we have to admit is not entirely their doing.

Our Nation as a Work in Progress

In the end, our experiences define how we perceive the world; nonetheless, it does not take a lot for us to understand and to empathize with other people. Moreover, it also does not take much for ignorance to shield our eyes from the truth. For us to think that something as complicated and as sensitive as the Martial Law period can be summarized by just a few people, when it was experienced by an entire country, is another form of ignorance altogether.

Each experience is as valid as the other; each opinion as valuable as the next. What we have to realize is that in the discussion of a topic as divisive as the Martial Law, it does not matter which account or side is right or wrong. What matters is that we are able to see beyond our own perspectives, beyond our own walls, because only then can we really begin an attempt on their demolition.

Written by Leanne Lacaden.

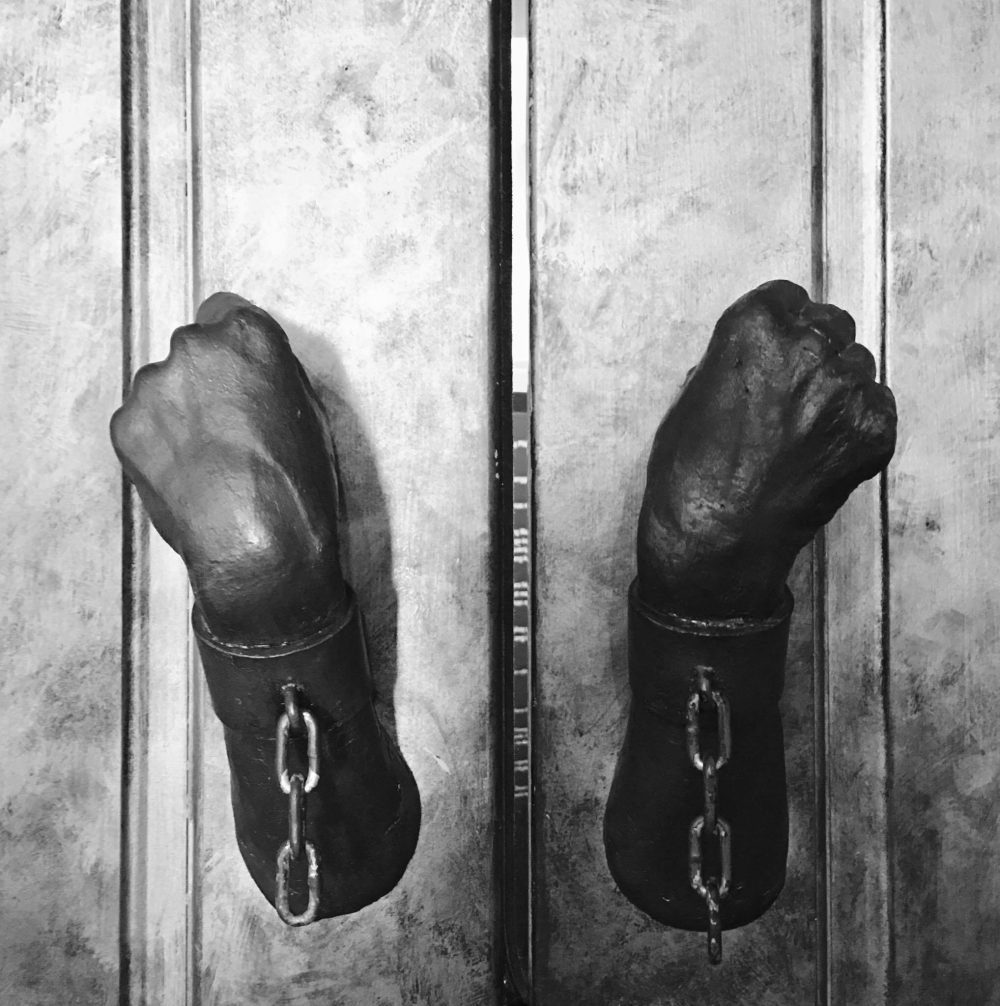

Photography by Tiffannie Litam.

See also other articles for our EDSA 31st Anniversary series: