Article by Ivan Sison

Edited by Nikka Gan and Regiena Siy

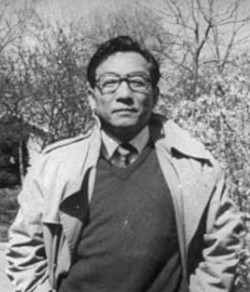

Hu Shuli

Given China’s long reputation of censorship, one would expect “Chinese investigative journalism” to be both an oxymoron and an impossibility, yet the legendary Mainland journalist Hu Shuli exemplifies that. With her hailing from a family of journalists, being a fellow of the World Press Institute of 1987, and her creation of the Caijing business magazine in 1998, she was already an established name. However, it was her exposés in the mid-2000s that made people call her “the most dangerous woman in Asia.” These exposés–which included the Chinese government’s cover-up of the SARS epidemic, deceitful business practices in the Shanghai’s stock exchange, and corruption in China’s biggest corporations–unseated officials both private and public, and forced reforms in the Chinese government and economy. [3] [4]

Her fact-centered and consistently well-informed coverage earned her accolades such as the Ramon Magsaysay Award and Missouri Honor Medal for Distinguished Service in Journalism. At present, Hu is a practicing journalist at Caixin Media (which she also founded), and a professor at the Sun Yat-Sen University. [5]

Hong Kong 2019 Protest Journalists

The wealthy city of Hong Kong was marred by one of its darkest periods in history. What started out as orderly pro-democracy protests in 2019 escalated into a spiteful war between police and civilian protesters. Hong Kong’s journalists had positioned themselves amidst the tear gas and molotovs, documenting the most dystopian scenes of civil unrest and police violence in recent memory.

Although shielded by Hong Kong’s constitution, the press were not protected from the horrors of the protests. Some encounters yielded them unhurt yet shaken, such as photojournalist Alex Chan’s 40-hour detainment for allegedly holding a counterfeit press card, and photojournalist Lam Yik having to witness special police forces brutalize an unarmed woman as they took her away. [6]

But some of these encounters did not leave them unscathed. Uniformed press reporters being subdued by police during reportage, such as Holmes Chan and fellow journalists being pepper sprayed at Mong Kok, were not uncommon incidents.[8] One of the most harrowing, however, is undoubtedly Gwyneth Ho’s. She became famous for continuing to livestream the violence at Yuen Long Station (known as the 721 Incident) despite being audibly beaten and pursued by an armed thug. [9] At present, the fate of Hong Kong journalism seems bleak under the National Security Law imposed by Beijing in 2020. [10]

With China’s strict censorship, Taiwan with Tsai Ing-wen as its leader is looking more like a democratic haven for exiled journalists. [13]

However, things were not always this way in the island nation. In the 1980s, Taiwan was in the era known as the White Terror, where the nation was under a martial law imposed during the rule of Chiang Kai-shek. [14] This oppressive one-party rule did not sit well with journalist Henry Liu, who moved to California in 1976 [15] to continue writing critically of the Taiwanese government under US freedom. Liu was a fearless and expressive writer. In fact, his most famous work was an unauthorized biography of Chiang Ching-kuo, the son of Chiang Kai-shek and leader of Taiwan at that time. Liu was warned in many ways by friends and officials to tone down his writing, but he would always scoff it off. [16]

On the morning of the 15th of October 1984, he would be found dead at his garage at the hands of members of the Bamboo Gang, a Taiwanese triad operating in the U.S. Investigations conducted by Taiwan and the U.S. pointed to Admiral Wang Hsi-ling, the head of Taiwan’s military intelligence agency, [17] [18] as the instigator of the plot. Henry Liu’s death rocked the trust of the Chinese diaspora in the States and US-Taiwan relations that decade.

As economies and communities become bigger, it becomes harder for any one person to have a complete image of what is happening in the world–especially if such information is kept secret or manipulated by major actors. Journalists are revered for keeping the public in the know, but for this reason, they are feared and are major targets for violence. To say the least, journalism is stressful work. Next time you watch a war coverage, or read a government expose, think about the journalists who put their health or even lives on the line to provide us with the news we comfortably consume daily.

Sources:

1. The White House (2021). The Constitution. [online] The White House. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/our-government/the-constitution/.

2.. Asia Society. (n.d.). President’s Circle Dinner with Hu Shuli. [online] Available at: https://asiasociety.org/hong-kong/presidents-circle-dinner-hu-shuli-0 [Accessed 22 Nov. 2021].

3. Ramon Magsaysay Award Foundation (n.d.). Hu, Shuli. [online] Available at: https://www.rmaward.asia/awardee/hu-shuli [Accessed 22 Nov. 2021].

4. Encyclopedia Britannica. (n.d.). Hu Shuli | Chinese journalist and editor. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Hu-Shuli.

5.United Way (n.d.). Hu Shuli | United Way Worldwide. [online] Available at: https://www.unitedway.org/about/leadership/hu-shuli# [Accessed 22 Nov. 2021].

6. Blind Magazine (n.d.). Hong Kong Photojournalists Look Back on Photographing the 2019 Protests. [online] Available at: https://www.blind-magazine.com/en/news/3702-hong-kong-photojournalists-look-back-on-photographing-the-2019-protests-en [Accessed 22 Nov. 2021].

7. Yik, L. (n.d.). Lam Yik. [online] The Wider Image. Available at: https://widerimage.reuters.com/photographer/lam-yik [Accessed 22 Nov. 2021].

8. Twitter. (n.d.). https://twitter.com/holmeschan_/status/1170581457430953984. [online] Available at: https://twitter.com/holmeschan_/status/1170581457430953984?s=20 [Accessed 22 Nov. 2021].

9. Hui, M. (n.d.). The journalist who livestreamed the Hong Kong protests’ darkest moment is now a dissident behind bars. [online] Quartz. Available at: https://qz.com/1987247/a-journalist-who-covered-hong-kong-protests-now-faces-life-in-jail/ [Accessed 22 Nov. 2021].

10. Tsoi, G. and Wai, L.C. (2020). China’s new law: Why is Hong Kong worried? BBC News. [online] 29 May. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-52765838.

11. Wikipedia. (2021). Henry Liu. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Liu [Accessed 22 Nov. 2021].

12.Bishop, K. and Times, S.T. the N.Y. (1987). Taiwanese to Be Tried in West in Murder of Writer. The New York Times. [online] 8 Mar. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/1987/03/08/us/taiwanese-to-be-tried-in-west-in-murder-of-writer.html [Accessed 22 Nov. 2021].

13. Olcott, E. (2021). Taiwan seizes chance to host foreign reporters kicked out of China. Financial Times. [online] 20 Apr. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/ab588fed-fc21-4b19-b601-538d87d79db3 [Accessed 22 Nov. 2021].

14. Taiwan Kuomintang: Revisiting the White Terror years. (2016). BBC News. [online] 13 Mar. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-35723603.

15. Google.com. (2016). Boca Raton News – Google News Archive Search. [online] Available at: https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=XjVUAAAAIBAJ&sjid=Oo0DAAAAIBAJ&pg=5609%2C6111101 [Accessed 22 Nov. 2021].

16. Butterfield, F. (1984). DEATH OF CRITIC OF TAIWAN LEADER STIRS FEAR AMONG CHINESE IN U.S. The New York Times. [online] 2 Nov. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/1984/11/02/us/death-of-critic-of-taiwan-leader-stirs-fear-among-chinese-in-us.html [Accessed 22 Nov. 2021].

17. Mathews, J., W.P.S.W. Staff writer, & Staff writer D.O. contributed to this (1985). Taiwan Admits Role in Murder Of U.S. Author. Washington Post. [online] 16 Jan. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1985/01/16/taiwan-admits-role-in-murder-of-us-author/5e98e4eb-6c60-47e7-8e51-8ac38c0d6dbf/ [Accessed 22 Nov. 2021].

18. Myers, R.H. (1989). A Unique Relationship: The United States and the Republic of China under the Taiwan Relations Act. [online] Google Books. Hoover Press. Available at: https://books.google.com.ph/books?id=lveO9Bk7cgAC&pg=PA40&lpg=PA40&dq=henry+liu+Wu+Kuo-cheng&source=bl&ots=1tJ01abR7N&sig=ACfU3U2Qcl7OoYZW9qMeOhIkF26yJsQVnw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjtvYOGmZ30AhUihlYBHRmLD1UQ6AF6BAgsEAM#v=onepage&q=henry%20liu%20Wu%20Kuo-cheng&f=false [Accessed 22 Nov. 2021].

This article is brought to you by the Communications and Publications department of Ateneo Celadon and Elements Magazine on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/CeladonElementsMagazine