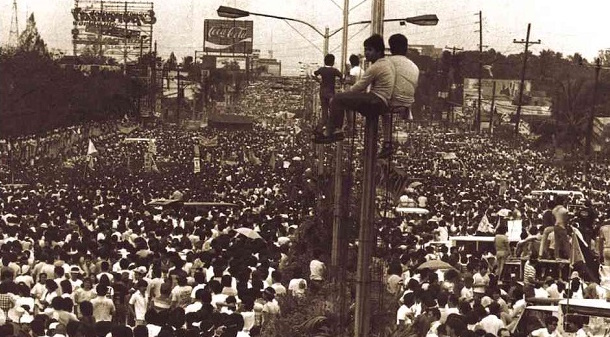

Thirty-one years ago, Filipinos from all walks of life came together in a massive demonstration of faith, unity and resolve that became known as the EDSA Revolution.

Among them was 22-year old activist, Freddie Young.

Unlike most of the Filipino activists at the time, however, Freddie was an ethnic Chinese. And that was unusual, because during that time, the ethnic Chinese preferred to stick to business and keep out of Philippine politics.

“It was partly because, for many ethnic Chinese then, even those who have already become Filipino citizens, this country was not yet ‘home’. In their minds ‘home’ was still somewhere else – maybe China, Taiwan or some mythical place. But not here.”

It might have been the same for Freddie had he not transferred to the Ateneo High School during his 3rd year. In 4th year, the school had a program called Tulong-Dunong (helping others to learn), which required the seniors to tutor underprivileged students in public schools. The bright, Grade 5 students Freddie taught did not have books, and were often hungry. Some wore tattered uniforms, and others walked a long distance to school everyday. The experience opened Freddie’s eyes to the reality of poverty in the country.

In college, Freddie came to realize that most of the poor were victims of unjust socio-economic structures that perpetuated poverty. And these unjust structures were in turn defended by the political system —the Martial Law regime that protected the interests of Marcos and his cronies. Many people who opposed the regime were jailed, tortured, killed—or they just disappeared.

Freddie became an activist. He joined a number of organizations, becoming the President at one point of the Political Society of Ateneo. He also began to organize among the urban poor in Tatalon, Quezon City.

Civil Disobedience

The 1986 Snap Elections was one of the dirtiest elections in Philippine history. Its levels of cheating, violence and intimidation were such that it convinced many Filipinos of the futility of electoral change. In its aftermath, opposition candidate Cory Aquino called for a nationwide civil disobedience campaign.

In the afternoon of February 22, 1986, Freddie was at a meeting with the heads of different organizations to plan activities in support of Cory Aquino’s call. In the middle of the meeting, the group received a message that Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile and AFP Chief of Staff Fidel V. Ramos have broken away from Ferdinand Marcos and were going to have a press conference in Camp Crame.

Although Freddie wanted the group to consider immediate mass action in support of the breakaway group, the others felt that it would be better to be cautious. They did not want to be caught in a crossfire between two military factions, both of which they were suspicious about. The meeting ended early, and everyone was asked to go home.

Instead of going home, however, Freddie first went to his girlfriend’s house, and it was there that he was able to listen to the press conference of Enrile and Ramos over Radio Veritas, the only local mass media outlet willing to broadcast it.

By the time Freddie got home, his parents had already found out about the trouble and forbade him not to go out of the house. He began calling up his friends and contacts, initially to share and verify news, and later to persuade them to go to EDSA, “Look, we need to do something. I’m going there; who’s going to go with me?” Many agreed to go.

Freddie also called up his urban poor leaders in Tatalon and conferred with them. Sometime after 9 p.m., he told the leaders: “Gather all the people that you can. Get as many jeeps as we can. Let’s go to EDSA.”

At about 10 p.m. Freddie quietly left home, without telling anyone in his family.

On the Grounds of EDSA

There were about 40 persons waiting for Freddie in Tatalon. They crowded into two rented jeepneys. Several people had to sit on the roofs of them. They proceeded to Cubao and marched to Camp Crame from there.

Freddie admitted feeling apprehensive. “That was something that really impressed itself upon my mind,” he said. “I made my decision. I can take responsibility for my life; but now I’ve also asked other people to risk theirs. If something goes wrong, it’s something I have to deal with for the rest of my life.”

The crowd at EDSA steadily grew. The urban poor group brought just a little food and water with them, but they had more than enough, because everybody that went to EDSA kept sharing what they had—sandwiches, water, junk food. They were enough for them to never went hungry or thirsty during the whole four days of the Revolution.

If something goes wrong, it’s something I have to deal with for the rest of my life.

However, the crowd began to thin during the first night. By early morning the next day (a Sunday), there was a time when there were approximately just 2,000 people on EDSA. Freddie found a payphone and began urgently calling people. “You better come, or else this is not gonna end well.”

“We knew it was dangerous,” he said. “The people were there knowing their lives were at risk, but we knew we had to be there. We felt the need to protect Enrile and Ramos from the forces loyal to Marcos. But at the same time, we needed to ensure that, if Marcos goes, no military junta takes power, and that Cory Aquino becomes president.”

Cardinal Sin, Butz Aquino and others made continuous appeals. Eventually, more people started coming.

All Walks of Life

“The people who went to EDSA came from all walks of life. Upper class, middle class, urban poor. Some were students, side-walk vendors, professionals. People from all stripes. People say it was all about the middle-class. It was not. I can be a witness to that,” Freddie says. “We all had our different stories, our little stories, our little lives. But this was something bigger, something we all cared about deeply. That’s why we were there.”

Unbeknownst to him, his parents came Sunday afternoon, realizing he was no longer at home. They could not find him there and left. However, it was the first time they realized the extent of the people in EDSA.

“You have to understand this was before Internet. Information at that time was all controlled. The only news source we had was Radio Veritas. The controlled media was trying to make people believe that EDSA was a small thing,” Freddie explains.

The people who went to EDSA came from all walks of life. Upper class, middle class, urban poor. Some were students, side-walk vendors, professionals. People from all stripes.

For him, Monday was the most nerve-wracking day of the Revolution. Marcos forces attacked the Libis area near Camp Aguinaldo in the early morning. They applied tear gas to disperse people before using troops. But they did not get that far.

Freddie was stationed near the gates of Camp Crame when he heard the sound of helicopters coming. “People thought, ‘That was it. Finally, they’re using air power. We’ll be attacked,’” he recounts.

“[But] lo and behold, the helicopters landed. They joined the rebels. That was the psychological turning point. It seemed to us like a big chunk of the Armed Forces was now joining the rebels.”

News Too Early

This was followed by a news announcement that Marcos had already left Malacañan Palace. Celebration erupted. Ecstatic, Freddie told the people from the urban poor community, “Let’s go back to Tatalon. Let’s leave now. Let’s walk around and tell people that Marcos is gone.”

Freddie’s group went back to Tatalon and marched through its streets, delivering the news that Marcos had left. However, moments after, people notified him that Marcos was on TV. It was later confirmed that the news of Marcos’ departure from power was premature.

“[The news] ‘Marcos was gone’ was the happiest moment of my life,” he said. “Akala naming wala na. After 20 years of dictatorship, after 20 years of hardship, wala na si Marcos. Only to discover that it was wrong.” (We thought it was all over. After 20 years of dictatorship, after 20 years of hardship, Marcos was gone. Only to discover that it was wrong.)

“We were really disappointed. I finally said, ‘Everyone, we have to go back. It might be a trap. We have to go back.’” They returned to EDSA.

Last of the Long Stretch

On Tuesday, Cory took her oath as President, but the people on ground were apprehensive whether Marcos would give up and leave, or fight. “I called up my parents,” he said. “Because there was a foreboding that something might happen.”

“Come back home first. I’ve prepared food, water, supplies. Put it in our van and bring it to EDSA, and share it with the people there,” his dad said.

Freddie was touched. He and his father did not see eye-to-eye on a lot of things. This support was something unexpected but very welcome. He took the supplies his dad prepared, went to EDSA and distributed them.

On the evening of that day, Marcos finally left. But this time the people wanted to be sure. The people at EDSA decided to march from Crame to Malacañan palace.

“It was a long distance away, but it felt like New Year. People were on the streets cheering. We should all be tired, but we felt energetic and alive.”

When they got to Malacañang, they saw how things were abandoned. There were papers all around, and a lot of food. Some of them who were hungry started taking the cans of biscuits that were there. After a while, soldiers of the “New Armed Forces of the Philippines” came to enforce order. They then left.

The Chinese-Filipino Experience

When Freddie recalls his experience, he still finds it incredible. “It was such a once-in-a-lifetime thing. But the amazing thing was the change in the attitudes of many people. They started caring more. My parents used to tell me that [the political situation in the Philippines] was not [the ethnic Chinese’] fault or responsibility. I could see their attitudes changing.”

The EDSA Revolution gave Freddie’s parents a shared experience with other Filipinos, and it gradually changed their views. He recounted an incident a few years ago regarding the Spratlys and Scarborough Shoal, which involved the Philippines and the People’s Republic of China. “We were watching television. And my mom said, ‘What is China trying to do? This is our land, this is our territory.’

“Surprised, I looked at her and asked, ‘Ma, what’s that again? Can you repeat what you just said?’ That’s when I knew that she found home. And I think that’s what we need to understand. It’s only when we realize we’re home—that this is home—will we have that heart to do things for it.”

The Values of EDSA Today

Remembering EDSA today gives a polarizing effect. There are those who acknowledge and respect its role in Philippine history for the exit of a dictator; and there are those who would understand it to be the removal of a great president. Freddie himself finds that the Cory administration was only able to bring some form of democracy to the country, but not a full democracy. That, however, does not deny the reality that Martial Law was worse. He also believes that differences in opinions are okay; however, a revision of historical facts is wrong, given that the evidence is there for everyone to verify.

“Please respect the facts. Don’t say ‘this is what happened in the past’ when, in fact, there’s evidence and data showing the contrary,” he said. “I consider it our failing for not being able to communicate [the experience of Martial Law] with the succeeding generations. We really need to rectify that.”

Don’t begin with strategy; begin with principle. You have to always do what’s right, even if it’s unpopular.

Today, Freddie advises our youth to engage the public in discussion. “It is a matter of showing to our people that the very ideals they want are in danger because of what’s happening now.” He also emphasizes the value of principle more than ever. “Don’t begin with strategy; begin with principle. You have to always do what’s right, even if it’s unpopular. If you begin by strategizing without considering whether it’s right or not, then that would be the wrong way of bringing about change in society.”

At the end of the day, the celebration of EDSA invites reflection, not just from those who experienced it, but also from those who have not. Its lesson was supposedly one of unity, but now some only see it as one of division. Whichever perspective one takes on EDSA, it is important that we do not ignore the historical facts behind the event and fabricate our own. We should always strive to understand what EDSA means to the living spirit of our nation, whatever our backgrounds may be. And we must remember that sometimes, the only way forward is to come home.

Written by Joshua Cheng, in collaboration with Frederick Young.

See also other articles for our EDSA 31st Anniversary series: