Article by Jadyne de Jesus

Edited by Nikka Gan

The sound of rolling dice in a ceramic bowl, passed around the round table in a Chinese restaurant is a common sight at this time of the year. To Chinese families, the dice game is an important part of the Mid-Autumn Festival, a traditional lunar celebration dedicated to their autumn harvest. However, the dice game is only one aspect of the festival’s tradition. What perhaps, can stand to be more interesting are the cultural backstories that stood as the inspiration to the festival, all of which are attributed to the moon as an aspect of their folklore.

As one of China’s oldest festivals, the Mid-Autumn Festival has multiple folklores to explain the occurrences that people could not understand back then. The myths with traces of reality intertwined in their stories illuminate the rich culture hidden in a festival that has carried over to modern times. The moon portrayed as the setting, or even the character for these tales, only further highlights the lunar aspect of the festivity. As such, it is the main reason why the Mid-Autumn Festival is always celebrated at night. Here are the six different versions of the folklore:

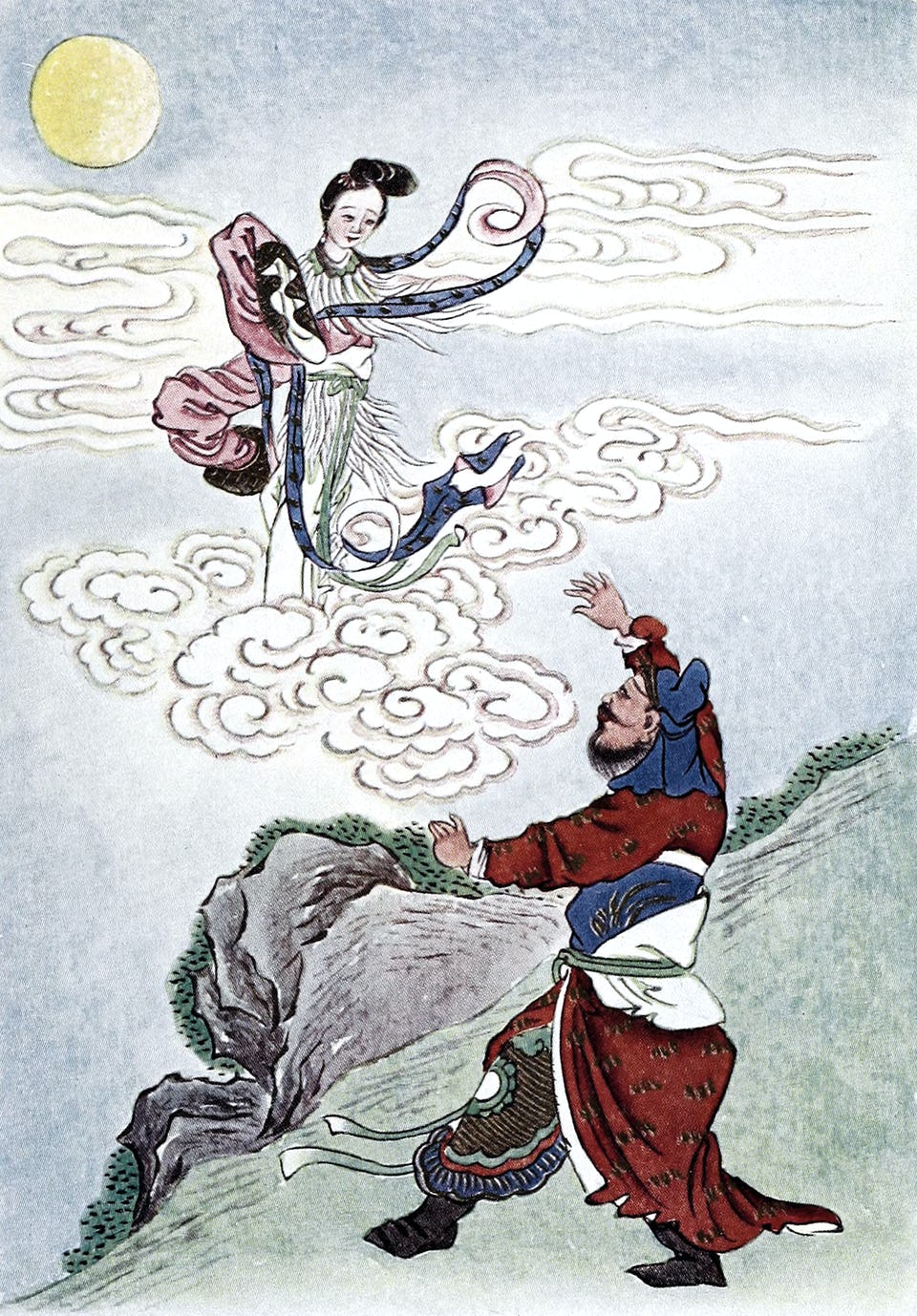

Chang’e and the Moon. Perhaps the most famous version of the folklore, the story revolves around the figure Chang’e. Back in ancient times, ten suns blazed throughout the day, which caused the people heavy distress. The warrior Hou Yi then brought salvation to the people by commandeering his bow and arrow to shoot down all the suns, sparing only one.

Time passed by and the notorious Hou Yi drew the attention of the Queen of Heaven, who planned to award him an elixir of immortality. The elixir granted eternal life, but on the condition that the drinker would immediately leave the mortal world for heaven. Hou Yi chose not to abide by the queen’s request and instead, brought it home. His wife, Chang’e, was alerted to this. She scoured for the elixir with interest. Instead of Hou Yi, Chang’e drank the elixir, and sacrificed her mortal life on Earth for an eternity in the heavens.

As she ascended, Chang’e aimed to settle on the moon as it was the closest place to Earth that she could reside in. The grieving Hou Yi was first livid with rage over his wife leaving him; however, he began to dearly miss her, so he began commemorating his wife by preparing a feast every full moon. Later, the dishes he prepared came to be the ones that we describe as Mid-Autumn Festival staples. Chang’e was then memorialized in legend as the Moon Goddess, and in other stories, referred to as the embodiment of the moon itself.

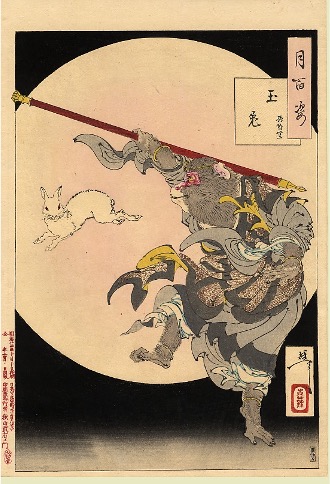

Rabbit on the Moon. Once, when a god was visiting the mortal world, he came across three animals and wanted to give them a test, so he transformed himself into an elderly man. The rabbit, along with a fox and monkey, were approached by the immortal in disguise, asking for something to eat. The fox and monkey gave up their food, but the rabbit did not have any to spare.

Nobly, the rabbit said that the elderly man could eat it instead and sacrificed itself by jumping into a fire. Honored by his character, the god memorialized the rabbit by saving him from the flames and sending him to the moon. This version of the folklore connects with the story of Chang’e as the rabbit is said to reside as the moon goddess’ companion in her Moon Palace, and also occasionally appears in other Chinese folklore.

Wu Gang Chops the Tree. Not necessarily related to the festival, this version touches on a myth widespread to mortals. In this version, a man named Wu Gang followed immortals to heaven and received immortality as well. However, along the way, he found himself banished from the heavens to spend the rest of his days on the moon, chopping a laurel tree in front of the Moon Palace. Every time he would chop the tree, it would grow back sturdier and taller, this only meant that his punishment was eternal. His story propagated a saying that if you looked at the dark side of the moon, you may still see Wu Gang chopping his laurel tree.

Li Longji and the Moon Palace. In Emperor Li Longji’s time, the Lunar Festival was already something they celebrated. The Emperor was particularly fascinated by the story of Chang’e and his desire to visit the Moon Palace. He, along with a master and priest, flew up to the clouds and landed on the moon. They were prohibited to enter the grounds of the palace as mortals, but the emperor parted ways with the celestial body with a song. Hearing the moon fairies sing a song, he retained the hum of the melody and composed the song ‘Melody of White Feathers Garment’ as tribute to his journey to the moon.

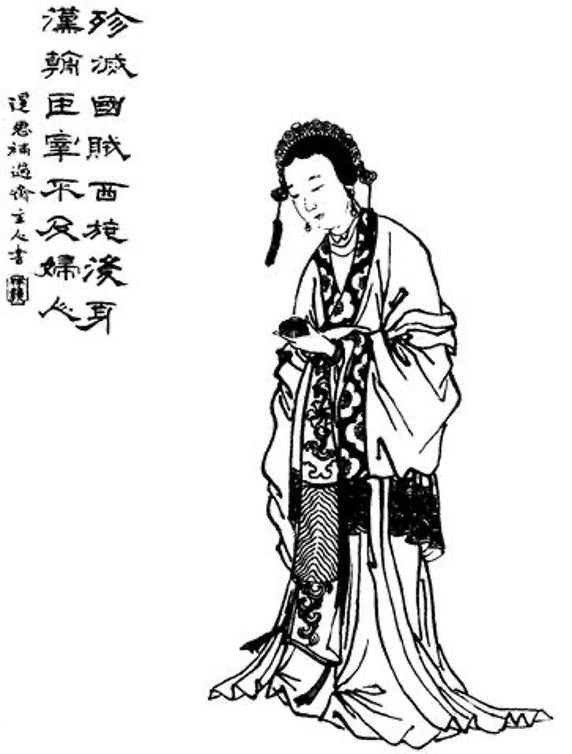

Diaochan Worshipping the Moon. A beautiful woman named Diaochan lived in a time of turmoil in the palace. With all the tension occurring with the royal court of her time, Diaochan turned to the moon for a sense of religious comfort. Chang’e, who observed Diaochan praying, could not help but become envious of her ethereal beauty. This cemented Diaochan’s beautiful visual in folklore, considered as a woman that even a goddess would envy.

Zhu Yuanzhang and the Mooncake Uprising. Unlike the other stories told, the story of the Mooncake Uprising is actually historically accurate. In a time of a restrictive government, Zhu Yuanzhang wished to unite the masses into a revolt, but because once their government kept an eye on everything the citizens did, communication became difficult. Zhu Yuanzhang’s counselor innovatively thought of passing messages through mooncakes as the Mid-Autumn Festival was nearing. The ingenious idea was a success, and ultimately led to the revolt that Zhu envisioned. As a result, mooncakes became a customary treat eaten every Mid-Autumn Festival.

These different versions of Chinese lunar folklore have surpassed centuries of storytelling, and are still being kept alive in some areas that deeply honor the ancient origins of the festival. In the Chinese-Filipino community, a scarce opportunity lies where one’s lips utter one of these said stories, but the tales will never be abandoned. Many superstitious elders still pass down these folktales to the next generations. With every arrival of the Mid-Autumn Festival comes a time wherein these stories can be kept alive and reignited as we look past the dice game, and look further into the stories embedded in our vast heritage.

This article is brought to you by the Communications and Publications department of Ateneo Celadon and Elements Magazine on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/CeladonElementsMagazine